Mono Symptoms: The Exhaustion Disease That Steals Months of Your Life

Understanding infectious mononucleosis — why "the kissing disease" hits harder than you think and what the exhaustion really means for your body

The fatigue arrives first, insidious and overwhelming. Not the tired feeling after a bad night's sleep or a busy week — something deeper, more totalizing. You wake up exhausted. You move through the day in a fog. By afternoon, climbing stairs feels like summiting Everest. And this isn't temporary. This is your life now, for weeks or months, courtesy of a virus most people dismiss as "the kissing disease."

Infectious mononucleosis — mono for short — ruins semesters, derails careers, and teaches hard lessons about the difference between being sick and being utterly depleted. It's caused primarily by the Epstein-Barr virus, and while it's rarely dangerous in healthy individuals, it's frequently devastating in ways that don't show up on most medical tests.

In November 2025, as college students push through midterms and young professionals grind through workplace demands, mono continues its quiet rampage through populations that can least afford to lose weeks of productivity. Understanding its symptoms isn't just medical trivia — it's recognizing when your body is demanding a timeout you can't negotiate your way out of.

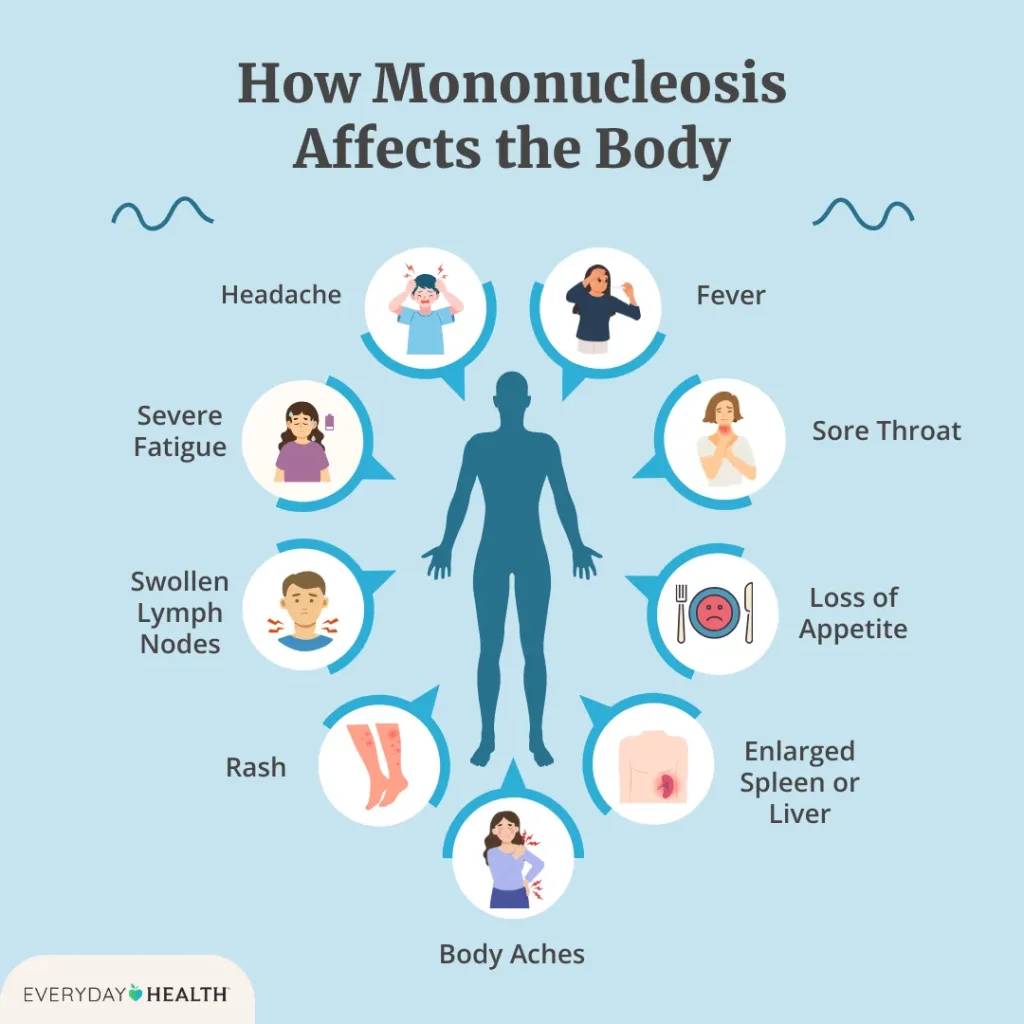

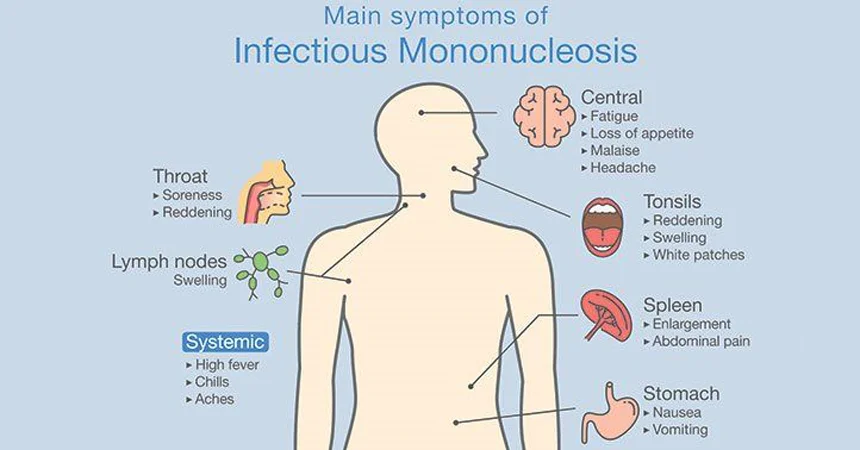

The Classic Mono Triad: Fever, Throat, Fatigue

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, mono typically presents with three hallmark symptoms that define the acute phase of illness:

Extreme fatigue: This isn't feeling tired. This is bone-deep exhaustion that makes basic tasks feel monumental. Patients describe it as moving through water, thinking through fog, existing in a state of perpetual depletion. The fatigue can persist for months after other symptoms resolve, fundamentally disrupting normal life in ways that frustrate patients and confuse people around them who think you should be "better by now."

Severe sore throat: Often described as the worst sore throat patients have ever experienced. The pharyngitis associated with mono can make swallowing painful enough to interfere with eating and drinking. The throat typically appears bright red with white patches, sometimes accompanied by enlarged, pus-covered tonsils that make even breathing uncomfortable.

Fever: Temperatures ranging from 100°F to 104°F are common, though not universal. The fever pattern in mono tends to be less predictable than in some other viral infections, spiking at irregular intervals and contributing to the overwhelming sense of illness that characterizes the acute phase.

But reducing mono to this triad oversimplifies a complex infection that manifests differently across individuals and often includes symptoms that surprise both patients and healthcare providers.

"Mono is one of those diseases where the textbook description doesn't capture the lived experience. The fatigue isn't just a symptom — it's a complete restructuring of what you're capable of doing each day."

— Infectious disease specialist quoted by Mayo Clinic

Beyond the Basics: The Full Symptom Picture

Mono's symptom profile extends well beyond the classic triad, creating a constellation of complaints that can initially confuse diagnosis:

Lymph Node Swelling

Enlarged lymph nodes, particularly in the neck, armpits, and groin, are nearly universal in mono. The nodes can become tender, prominent enough to be visible, and sometimes alarming enough to prompt cancer concerns. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, these swollen nodes reflect the immune system's aggressive response to Epstein-Barr virus and typically resolve gradually over weeks.

Spleen and Liver Enlargement

Approximately half of mono patients develop splenomegaly — an enlarged spleen that creates risk for rupture if subjected to physical trauma. This is why doctors advise against contact sports and heavy lifting for weeks after diagnosis. Some patients also experience hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) and mild hepatitis, causing right upper abdominal discomfort and occasionally jaundice.

The spleen concern isn't theoretical fear-mongering. Splenic rupture, while rare, represents a genuine medical emergency that can occur spontaneously or following relatively minor abdominal trauma. It's the reason mono patients get stern warnings about avoiding physical activity — advice that's difficult to follow when you're young, athletic, and frustrated by forced inactivity.

Skin Rash

A small percentage of mono patients develop a rash, either from the virus itself or, more commonly, from taking amoxicillin or ampicillin antibiotics. The characteristic red, blotchy rash that appears when someone with mono takes these antibiotics is so reliable that it's sometimes used as a diagnostic clue. The rash isn't dangerous, but it's distinctive and adds another layer of discomfort to an already miserable illness.

Headache and Body Aches

Muscle aches, joint pain, and headaches accompany mono with enough frequency that patients initially suspect flu. The quality of discomfort differs slightly — mono's aches tend to be accompanied by that characteristic profound fatigue that flu doesn't usually produce to the same degree — but distinguishing between viral illnesses based on subjective symptoms alone is notoriously difficult.

Loss of Appetite

The combination of severe sore throat, general malaise, and sometimes nausea makes eating unappealing. Weight loss during acute mono is common, though rarely dangerous in otherwise healthy individuals. The challenge becomes maintaining adequate hydration and nutrition when swallowing is painful and appetite is absent.

The Timeline: How Mono Unfolds

Understanding mono's typical progression helps patients and families calibrate expectations — crucial for an illness where unrealistic timelines create frustration and delayed return to activity can feel like personal failure.

Incubation period (4-6 weeks): After exposure to Epstein-Barr virus, most people experience no symptoms for approximately a month. You're infected, potentially infectious, but feel completely normal. This long incubation period contributes to mono's spread — people transmit virus before they know they're sick.

Prodrome (several days): Vague symptoms emerge — fatigue, malaise, low-grade fever, mild headache. Nothing distinctive enough to suggest mono specifically, but enough to feel "off" in ways that prompt people to push through rather than rest.

Acute illness (1-2 weeks): The full symptom complex arrives. Severe sore throat, high fever, profound fatigue, swollen lymph nodes. This is when most people seek medical care, get diagnosed, and realize they're facing weeks of illness rather than days.

Recovery phase (2-4 weeks): Fever and sore throat gradually resolve. Lymph nodes shrink. Energy returns incrementally, though "recovery" is relative — most patients remain significantly more fatigued than baseline for weeks after acute symptoms resolve.

Post-infectious fatigue (weeks to months): This is where mono becomes particularly frustrating. The sore throat is gone, fever has resolved, but the exhaustion persists. Not the dramatic fatigue of acute illness, but a diminished energy reserve that makes normal schedules difficult to maintain. Some patients experience this fatigue for months, occasionally longer.

Why Mono Hits Young Adults Hardest

Mono earned its reputation as a disease of teenagers and young adults not because Epstein-Barr virus preferentially infects this age group, but because of when primary infection typically occurs and how symptom severity correlates with age at infection.

Most people encounter Epstein-Barr virus during childhood, experiencing either no symptoms or mild illness that's never diagnosed as mono. When primary infection is delayed until adolescence or young adulthood, the immune response becomes more robust and symptoms more severe. The classic mono syndrome is essentially an age-dependent manifestation of Epstein-Barr virus infection.

This creates ironic timing: mono tends to strike during life phases when people can least afford prolonged illness. College students miss exams and fall behind in coursework. Young professionals burn through sick leave and worry about career implications. Athletes lose training time during crucial seasons. The disease arrives precisely when societal and personal expectations demand peak performance.

Diagnosis: Why It's Not Always Straightforward

Diagnosing mono typically involves clinical evaluation plus laboratory testing. The heterophile antibody test (Monospot) is quick and commonly used, but it has limitations — it can be negative early in illness and occasionally remains negative throughout infection despite classic symptoms. More specific Epstein-Barr virus antibody testing can confirm diagnosis when Monospot results are ambiguous.

Complete blood counts in mono patients typically show characteristic patterns: elevated lymphocytes, including atypical lymphocytes that reflect the immune system's response to viral infection. Liver function tests may show mild elevations indicating hepatic involvement.

But diagnosis isn't always immediate or certain. Early in illness, tests can be negative. Symptoms overlap with strep throat, requiring throat cultures to rule out bacterial infection. Occasionally, mono masquerades as other conditions, leading to diagnostic delays that frustrate patients convinced something is seriously wrong but unable to get definitive answers.

"We tell patients that mono diagnosis is like solving a puzzle. Clinical picture, timing, lab results — they all have to fit together. Sometimes that takes a few days and repeat testing."

— Family medicine physician in clinical practice interview

Treatment: The Frustrating Reality

Here's the truth about mono treatment that frustrates every patient who hears it: there isn't one. Mono is viral, which means antibiotics don't help. No antiviral medications have proven effective for uncomplicated Epstein-Barr virus infection. Treatment is entirely supportive — rest, fluids, pain relievers for throat discomfort and fever, and patience.

For people accustomed to medical interventions that fix problems, this non-treatment feels inadequate. But it reflects biological reality: your immune system must clear the virus on its own timeline, and that timeline isn't negotiable regardless of how inconvenient it might be.

The practical treatment recommendations include:

- Rest: Not optional, not negotiable. Profound fatigue is your body demanding resources for immune function rather than daily activities

- Hydration: Particularly important when sore throat makes drinking painful but fever increases fluid needs

- Pain management: Acetaminophen or ibuprofen for throat pain, fever, and body aches

- Activity restriction: Avoiding contact sports and heavy lifting until spleen returns to normal size, typically 4-6 weeks minimum

- Gradual return to activity: Slowly rebuilding stamina rather than attempting immediate return to pre-illness activity levels

When Mono Becomes Complicated

Most mono cases, while miserable, resolve without serious complications. But certain scenarios require closer monitoring or intervention:

Airway obstruction: Severe tonsillar enlargement can occasionally compromise breathing, requiring corticosteroids or rarely hospitalization for airway management.

Splenic rupture: Though rare, this life-threatening complication causes sudden severe abdominal pain and requires emergency surgical intervention.

Neurological complications: Rarely, Epstein-Barr virus affects the nervous system, causing meningitis, encephalitis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Hematologic complications: Unusual but documented complications include severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, or hemolytic anemia requiring specialized treatment.

Chronic active EBV infection: A rare syndrome where the virus isn't adequately controlled, causing prolonged illness requiring immunological evaluation and sometimes aggressive treatment.

Living Through Mono: The Psychological Dimension

What medical descriptions of mono symptoms rarely capture is the psychological toll of profound, prolonged fatigue. When exhaustion becomes your defining characteristic for weeks or months, it affects more than your schedule — it affects your identity, your relationships, and your understanding of your own body.

Students fall behind academically, sometimes requiring medical withdrawals that delay graduation. Young professionals worry about career implications of extended absence or diminished productivity. Athletes watch teammates continue training while they're sidelined, unable to maintain conditioning they spent years building.

The frustration compounds when recovery doesn't follow a predictable trajectory. Some days feel slightly better, creating hope that the corner has been turned, only to have crushing fatigue return the next day. Well-meaning people offer advice about "pushing through" or suggest that lingering fatigue must be psychological rather than physical.

This psychological dimension parallels challenges faced in other contexts where invisible conditions create misunderstanding. Whether it's the prolonged rehabilitation following serious injuries that sideline athletes or the mental endurance required to persist through extended challenges, the gap between external perception and internal reality creates isolation.

Prevention: Can You Avoid Mono?

Given that Epstein-Barr virus spreads through saliva — hence "the kissing disease" nickname — complete prevention is unrealistic for most people. The virus transmits through kissing, sharing drinks or utensils, or close contact with respiratory secretions from infected individuals.

Practical risk reduction includes avoiding sharing drinks, food, or personal items with people who have active mono. But the long incubation period and the fact that people can shed virus before symptoms appear makes prevention challenging. Most transmission probably occurs before anyone knows they're infectious.

No vaccine exists for Epstein-Barr virus, though research continues. The virus's ability to establish lifelong latent infection after primary infection makes vaccine development complex. Even after recovering from mono, you harbor dormant virus that occasionally reactivates and can potentially transmit to others, though typically without causing symptoms in you.

The Takeaway: Respecting What Your Body Demands

Mono symptoms teach an uncomfortable lesson that modern life resists: some things can't be rushed, negotiated, or willed away through determination. Your body will take the time it needs to clear this infection and recover functional immune homeostasis. Fighting that timeline doesn't accelerate recovery — it just adds frustration to exhaustion.

For young people especially, mono forces confrontation with physical limits that previous life experience hasn't required acknowledging. You've always pushed through fatigue before. You've always caught up after illness. You've always bounced back quickly. Until you don't. Until your body simply refuses demands that exceed its current capacity.

That's not weakness or failure. It's biology asserting itself against schedules and expectations that don't account for the reality that you're human, and humans have limits. Mono symptoms aren't obstacles to overcome through willpower — they're information about what your body needs, delivered in terms that can't be ignored.

Understanding those symptoms — recognizing mono early, accepting the recovery timeline, respecting activity restrictions — doesn't make the experience pleasant. But it makes it manageable, and it prevents the complications that arise when people try to pretend they're not as sick as they actually are.

Because at the end of it all, mono is temporary. The fatigue eventually lifts. Energy returns. Life resumes. But how you navigate the illness affects how long that takes and how completely you recover. Sometimes the wisest response to overwhelming symptoms isn't fighting harder — it's finally listening to what your body has been trying to tell you all along.

Related Articles